Personal Reflections:

My son:

My son’s first story consisted of a series wavy lines and curlicues written in black marker across the back of a leather sofa. Upon completion, he declared, “Look! I wrote my story in grown up writing!” (For those of you who are wondering, yes, it was a permanent marker.)

With great pride, he read us his story. As he pointed to each “word” he shared an action packed and well developed account of Spiderman’s most recent adventure. While the writing itself was unreadable to anyone else, every other trait of writing was there: ideas, organisation, voice, word choice, sentence fluency. It was clear that my son was a writer – he just had to learn how to share his stories with others. As a mother, I hoped that the formal school instruction in spelling, spacing, and letter formation wouldn’t overshadow his enthusiasm for writing stories.

My daughter:

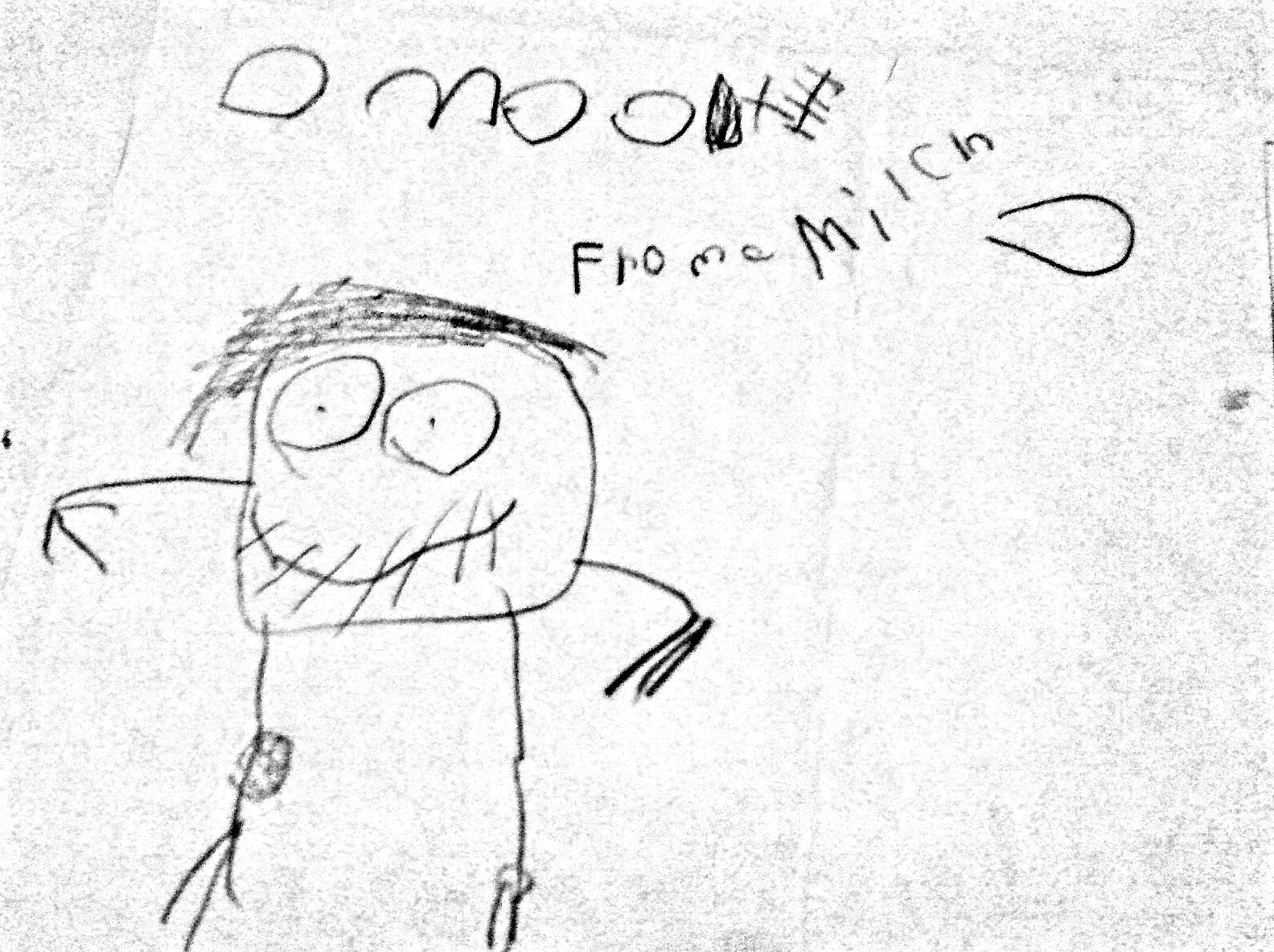

While my son’s first story was lost with the eventual replacement of the sofa, my daughter’s first piece of formal writing, a letter to her dad – wishing him a speedy recovery from knee surgery – survived:

I think you’ll agree that my daughter’s letter provides the reader with a clear sense of the event, the details of the event, and the impact of the event. (And yes, that’s just what her dad looked like when he came home from the hospital.) She was also using some of the conventions of text – a greeting at the top of the page:

![]()

and a closing:

![]()

This somewhat misplaced grouping of letters:

![]()

![]() is actually evidence of an almost correct spelling of her name, which is Michèle. (Yes, her name is presented on two lines rather than one, there are a few extra horizontal lines in the “E”, but she had a clear sense of using letter shapes to share her ideas)

is actually evidence of an almost correct spelling of her name, which is Michèle. (Yes, her name is presented on two lines rather than one, there are a few extra horizontal lines in the “E”, but she had a clear sense of using letter shapes to share her ideas)

Michele was also editing her work, which is clear when she realised she’d made a mistake:

![]() .

.

Young children are writers

The point of this is: as children begin drawing or using some form of letters to share their ideas, they are writers. Early years teachers acknowledge these these early can dos, encourage more exploration, and provide timely guidance focussed on the next steps:

1. Begin with talking about the story:

- Ask them to read the story to you and listen carefully.

- Respond to the reading with questions about the details.

2. Provide feedback about the can dos:

- the content of the story

- some element of the conventions (letter formation, spelling, spacing, etc.) that is developing well

3. Keep notes focussed on the known and next steps. When the time is right, use these notes to plan the next lesson that builds on these accomplishments.

The process described above is not only student responsive, it’s recursive. While the examples above illustrate the youngest of writers, this responding and feedback loop provides the foundation for writing instruction throughout a person’s writing career. Learning to write takes time, practice, instruction, and ongoing feedback about what’s been accomplished and what’s next. Effective support maintains the early joy of sharing a story by focusing on the student’s learning, interests, and voice.

Is spelling important?

One key point to consider: Correct spelling is a component of good writing, not a definition of good writing, so encourage children to explore and develop their ideas through interesting word choice and sentence structures as they learn how to spell.

Using a rubric to search for evidence of writing

If you’re not sure what the developmental progression of writing looks like, check out Education Northwest Grades K-2 Illustrated Rubric K-2.

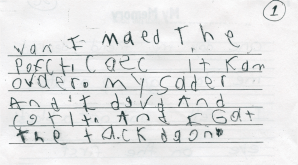

Now, give this process a try. Here’s a sample of a student’s writing. The writing prompt was: Write about a special thing that happened to you. Unfortunately, there’s no recording of the student reading the story aloud, so here’s a hint – the story is about a memorable game the student played.* Keeping all of the traits of writing in mind (ideas, organisation, voice, word choice, sentence fluency, conventions, and presentation) search carefully for the can dos and the what’s nexts”.

Here’s a transcription of the story, but try not to look until you’ve worked through the process:

When I made the perfect catch it came over. my shoulder and I dived and caught it. And I got the touchdown.

SO, is this student a writer? What does he know about writing? What will be most helpful to know next?

Discussion Guide to Accompany

Becoming a Writer:

What We Can Learn From a Child’s First Stories

Aligned with Universal Design for Learning (UDL) and Culturally Responsive Pedagogy

Purpose

This discussion guide supports teachers in:

- Reframing how we define “writing” in the early years

- Identifying students’ can dos across all traits of writing

- Practicing responsive feedback that builds on what the student has learned thus far

- Separating conventions from meaning-making without diminishing either

- Honoring students’ cultural, linguistic, and experiential knowledge as assets (CRP)

- Designing writing instruction that offers multiple entry points and pathways for success (UDL)

Opening Reflection

Individual Think

Think about the earliest piece of writing you remember from a student—or from yourself.

- What made it “writing” in your mind at the time?

- Whose definition of writing were you using—yours, the school’s, or the child’s?

CRP Lens:

How might culture, language, or home experiences have shaped how that writing was expressed?

UDL Lens:

What modes (drawing, oral storytelling, symbols, movement) were available—or unavailable—for expressing ideas?

Pair or Table Share

- How have your ideas about what counts as writing changed over time?

- What tensions do you notice between enthusiasm for writing and expectations around conventions?

- Where do those expectations come from?

Text-Based Discussion

Use the blog post Becoming a Writer: What We Can Learn From a Child’s First Stories as a shared text.

Discussion Questions

- What stands out to you about the son’s “story” written on the sofa?

- Which traits of writing were clearly present, even though the text wasn’t conventionally readable?

- What instructional risks does the author name regarding early writing instruction?

- How does the daughter’s letter demonstrate development beyond letter formation and spelling?

Facilitator Prompt

- Where do you see evidence of intentional communication in both examples?

- How might these examples look different—or be misinterpreted—through a deficit lens?

CRP Connection:

How does valuing intention over correctness affirm students whose language practices differ from school norms?

UDL Connection:

How does this blog model multiple means of expression and engagement?

Exploring the Writing Process Described

Review the three-step process outlined in the post:

- Begin with talking about the student’s writing

- Provide feedback about the can dos

- Keep notes focused on knowns and next steps

Group Discussion

- How does this process differ from how writing is sometimes assessed or responded to in classrooms?

- Why is beginning with the student’s writing so important?

- What makes this process recursive rather than linear?

CRP Lens:

How does beginning with the story center student voice, identity, and lived experience?

UDL Lens:

How does this process reduce barriers by separating meaning-making from transcription demands?

Reflection Question

- At what points in your instruction do conventions begin to overshadow meaning?

- Who is most impacted when that happens?

Applied Practice: Analysing Student Writing

Introduce the student writing sample connected to the prompt

Write about a special thing that happened to you.

CRP Note:

“Special” is intentionally open-ended, allowing students to draw from home, community, cultural, and personal experiences.

Step 1: Silent Review (Without Transcription)

Teachers examine the writing sample.

Guiding Lens

Keep all traits of writing in mind:

- Ideas

- Organization

- Voice

- Word Choice

- Sentence Fluency

- Conventions

- Presentation

UDL Reminder:

Focus on what the student is communicating, not just how it is encoded.

Step 2: Identify the Can Dos

In pairs or small groups:

- What does the student already know how to do as a writer?

- Where do you see evidence of meaning, structure, or intention?

- What conventions are beginning to emerge?

Record responses under:

“What the student can do”

CRP Check:

Are we naming assets before needs?

Are we avoiding comparisons to a single “normed” pathway?

Step 3: Identify What’s Next

Still working in groups:

- What would be a logical next instructional step?

- What feedback would support growth without diminishing confidence?

- What would you teach next—whole group, small group, or individually?

Record responses under:

“What the student is ready to learn next”

UDL Consideration:

What options could be offered for practice (oral rehearsal, drawing, shared writing, sentence frames)?

Step 4: Reveal the Transcription

After discussion, share the transcription.

Reflect

- How did hearing the intended message change (or confirm) your thinking?

- What might be lost when we assess writing without student voice?

- Whose voices are most likely to be misunderstood or undervalued?

Classroom Connections & Next Steps

Whole-Group Reflection

- How does this process support equity in writing instruction?

- What shifts might be needed in assessment, feedback, or planning?

- How can this approach help maintain joy in writing while still moving students forward?

CRP Summary:

This approach resists deficit narratives and affirms students as capable meaning-makers.

UDL Summary:

This approach widens access by honoring variability in how writing develops.

Action Planning

Ask teachers to complete the sentence:

“One thing I will try in my classroom as a result of this discussion is…”

Encourage specificity tied to feedback, assessment, or instructional routines.

Key Takeaways to Reinforce

- Children are writers as soon as they attempt to communicate ideas through marks, drawings, or letters.

- Correct spelling is a component of good writing—not its definition.

- Responsive instruction starts with meaning, builds on strengths, and targets next steps.

- Valuing student voice is both an instructional move and an equity stance.

- This feedback loop supports writers at every stage, not just in the early years.

Optional Extension

Use the Education Northwest Grades K–2 Illustrated Writing Rubric to:

- Locate the student’s current development

- Validate observed can dos

- Plan instruction aligned to the next stage of growth

- Discuss how rubrics can be used as guides, not gatekeepers