——————————————————-

Reframing Disengagement to Re-Engage Learners

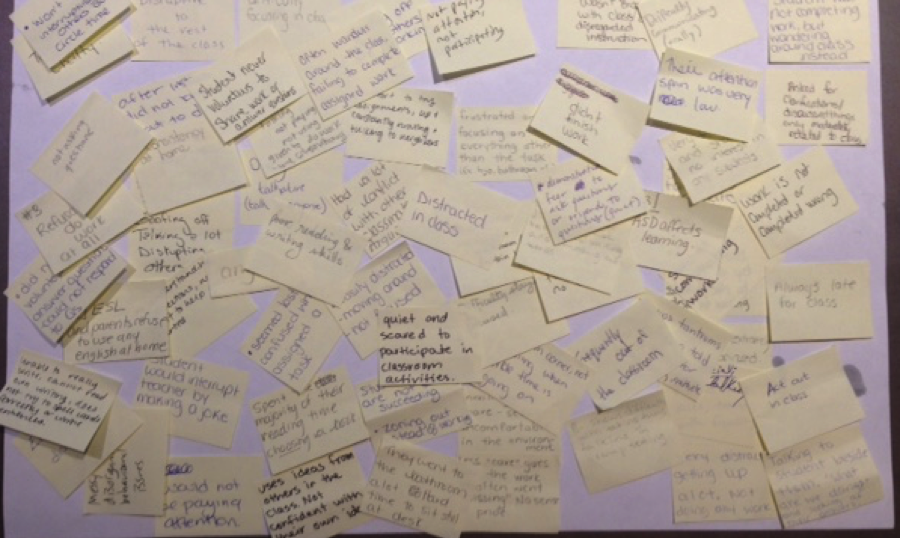

At the beginning of a recent professional learning session focussed on re-engaging disengaged students, we asked participants to use a post to describe a disengaged learner using just a few words.

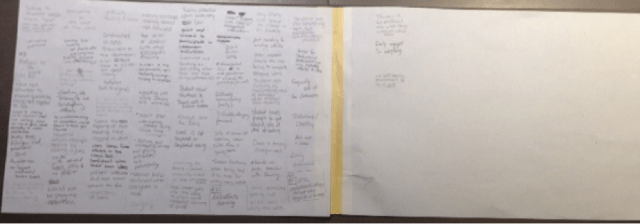

As participants had coffee and chatted, we sorted the Post-its into two columns.

On the left, the comments focused on problems: distracted, late, incomplete work, disruptive, not focused, poor writing, interrupts the teacher, frustrated, leaves the classroom, frequent tantrums, has ADHD.

On the right, the comments focused on potential: thinks abstractly, strong communication skills, works well in quiet settings, easily engaged.

The imbalance was striking. Most of what we notice—and name—about disengaged students centres on what’s wrong, not what’s possible. It was a powerful reminder that we need to reframe our perspective on disengagement.

We know this matters. But in today’s busy, diverse classrooms, how do we do it?

Here are a few starting points:

- Don’t make assumptions. Disengagement can happen to any student, regardless of background or past achievement.

- Look beyond the score. Study student responses, not just grades. Even low marks reveal “the known”—what a student can already do.

- Name strengths for the student. Keep it simple and honest: “I noticed you can… The next step is…”

- Learn what matters to them. Regardless of the age or subject, a student’s known, interests and experiences are powerful entry points for learning across subjects. What does the student know about? What are they curious about? This information can inform units of study that integrate several subject areas. For example: If a student’s interest is hockey, the possibilities for lessons in various subject areas include: comparing scores, examining the physics of a body check, determining the economic impact of hockey on the family budget, comparative studies of sports throughout the world, reading fiction and nonfiction accounts of hockey players, and using the texts and language of hockey as anchors for reading, writing, grammar, word work lessons. The possibilities are limitless.

- Design just-right challenges.

Create learning experiences that stretch students from what they already know to a point where they can see progress. This aligns with Vygotsky’s Zone of Proximal Development (ZPD), a recursive process that requires ongoing adjustment. This aligns with Vygotsky’s zone of proximal development (ZPD), a recursive progress that requires ongoing adjustment.

- Stay focused on re-engagement. Set high expectations, monitor progress, provide feedback, and adjust pedagogical practice when learning stalls

Want to see how this shift looks in a real school setting? Click here.

Beyond the Apple Discussion Guide: Reframing Disengagement to Re-Engage Learners

Facilitator’s Note: The blog post for this discussion follows this Discussion Guide. Do not share the blog post until after Section 1 is completed.

Purpose

This discussion guide supports educators in examining how disengagement is perceived, named, and addressed in classrooms. It encourages a student responsive mindset and practical strategies for re-engaging learners.

1.Opening Reflection

Prompt

- When you hear the term “disengaged student,” what words or images come to mind?

Activity Option

- Individually, write 3–5 words you associate with disengaged learners.

- In small groups, sort the words into two categories: Challenges and Potential.

- Discuss: Which category fills up faster? Why?

Read the blog post found at the end of this discussion guide.

- Examining Our Lens

Discussion Questions

- What stood out to you most about the balance / imbalance between the two Post-it columns in your group and in the blog post?

- Why do you think problem-focused descriptors tend to dominate our thinking?

- How might this lens influence our expectations, instructional choices, or relationships with students?

Facilitator Note

Acknowledge that noticing challenges is part of our role—but reframing allows us to respond more productively.

- Moving From Disengagement to Engagement

Discussion Questions

- Which of the “starting points” in the post resonates most with you?

- Which feels most challenging to implement consistently?

- How do you currently identify and name strengths in disengaged students?

Quick Practice

- Think of a student you consider disengaged.

- Complete this sentence:

“I noticed you can… The next step is…” - Share examples in pairs or small groups.

- Learning What Matters to Students

Discussion Questions

- How well do you know your students’ interests and experiences?

- How are, or could be, these interests currently reflected (or not) in your curriculum?

- What barriers exist to designing learning around student interests?

Application Activity

- Choose one student interest (e.g., sports, music, gaming, social media, the arts).

- Brainstorm 2–3 ways that interest could be integrated into your subject area.

- Share ideas across groups to build a collective bank of possibilities.

- Designing for Re-Engagement

Discussion Questions

- What does a “just-right challenge” look like in your classroom?

- How do you know when a student is in their Zone of Proximal Development?

- What adjustments do you make when learning stalls?

Reflection Prompt

- What is one instructional practice you could adjust this week to better support re-engagement?

- Commitment to Action

Individual Reflection

- What is one small, intentional shift you will try with a disengaged learner?

Optional Share-Out

- Invite volunteers to share their commitment.

- Consider revisiting these commitments in a future session.

Closing Thought

Disengagement is not a fixed trait—it’s a signal. When we shift our lens from what’s wrong to what’s possible, we create new pathways for learning, connection, and growth.